Makin’ a Myth: Charley Benger and the Myth of Black Confederates

Whether or not Black men served in the Confederate armed forces during the Civil War, as well as their roles, has been a subject of debate for decades. This debate recently emerged here in Macon, as a Civil War heritage group proposed donating a plaque to Macon-Bibb in honor of Charley (also referred to as Charles) Benger, a Black musician who played for the Confederate army during the Civil War. The plaque would’ve been installed in Rose Hill Cemetery. The heritage group, the local NAACP, and other Black leaders have been asked to meet to

What is known of Charley Benger’s life is documented in various primary resources, such as military records and newspapers. Collectively, they paint a complicated, and depending on the interpretation, sometimes contradictory portrait of who he was as a man.

According to Confederate military records, Charles Benger enlisted in the Confederacy on April 20, 1861, in Macon. He is listed as a musician. Records indicate that he was paid three times that year: June, August, and October. He was discharged on July 20, 1862.

What is missing from the current narrative is that Benger apparently re-enlisted on October 12, 1862 in Chatham County, Georgia.

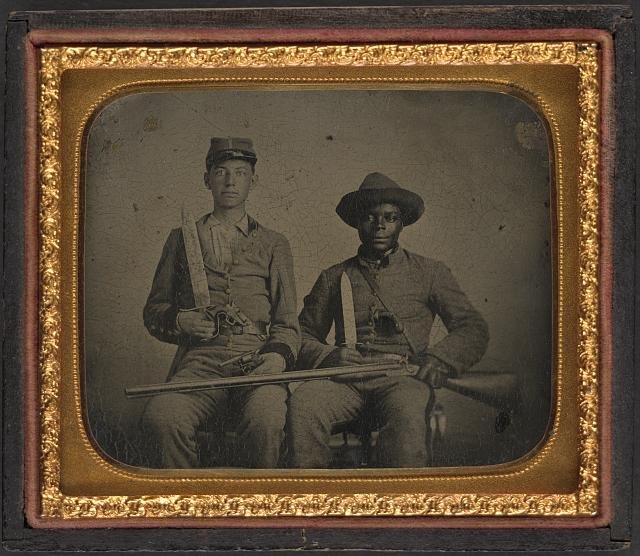

A record of payment for Charley Benger. Note the remarks: “musician by consent of his master.”

US, Civil War Service Records available on fold3.com state that Benger was paid for September and October 1862 and joined as a musician “by consent of his master.” That notation contradicts the statement in Benger’s 1880 obituary in the Macon Telegraph (see below) that he was “never a slave,” suggesting that he was an enslaved person and served with the permission of his enslaver.

An article from the Macon Telegraph reporting the death of Charley Benger.

The Macon Telegraph article above also states that Benger “enjoyed a pension from his old company.” This claim is interesting and bears further investigation. According to the National Archives and Records Administration, Georgia began offering pensions to former Confederate soldiers who had lost a limb in 1877. As time passed, pensions were granted to additional groups. For example, other disabled veterans or their widows became eligible for pensions in 1879. It was not until 1894 that old age and other disabilities were considered, well after Charley Benger, who reportedly died of old age, passed away in 1880. A thorough search of Confederate pension applications did not reveal a pension application on Benger’s behalf, nor for this widow.

How can we understand this complex situation? Tune in to the latest episode of the Makin’ Black History podcast to learn more as we discuss this topic with Kevin Levin, author of Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth (University of North Carolina Press, 2019).